An Essay by Charles Amos Horn.

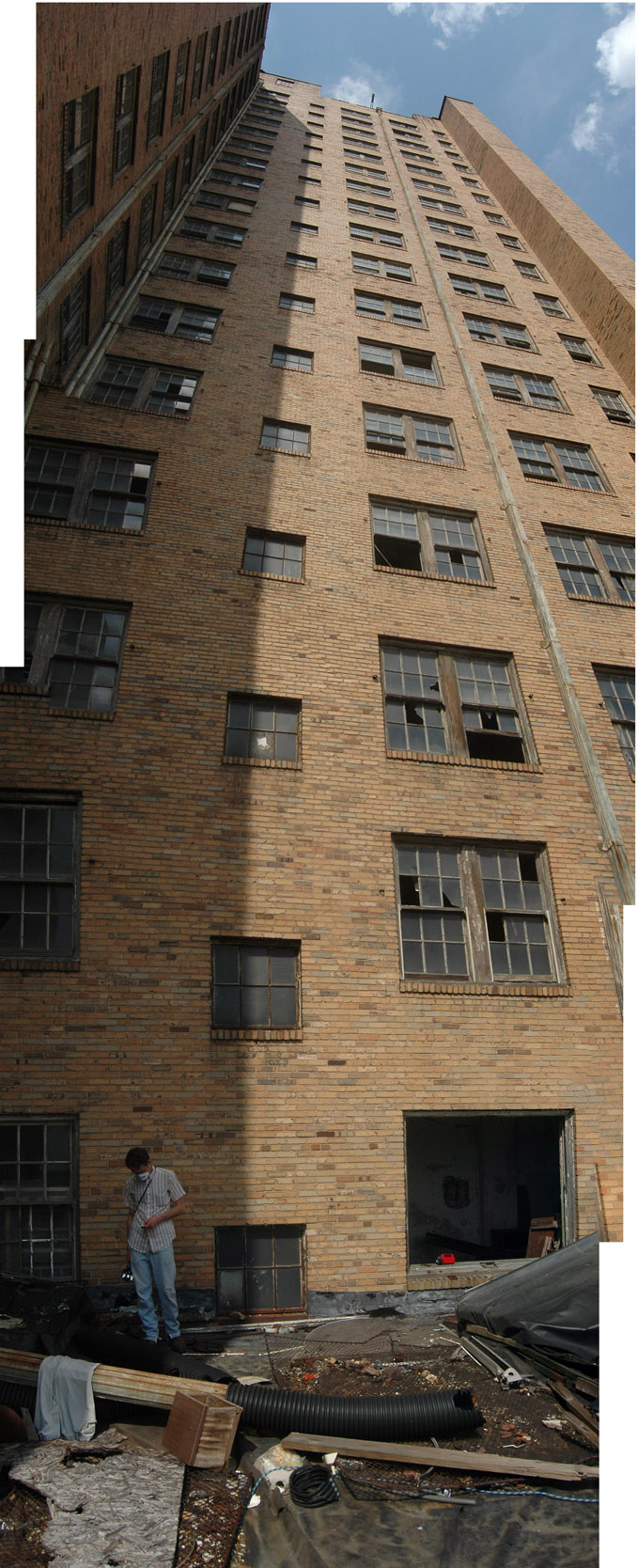

To get into the Leer Tower, one must squeeze through one of two 18" x 18" openings. I passed my camera through to Amos, and sort of dove in, legs first. The first thing my feet encountered in the dark was mushy, saturated cardboard. After our eyes adjusted and we found our flashlights, we carefully picked our way across the large storage room we found ourselves in. There was a foot of water standing on the floor in the lowest places, so we had to clamber from stacked doors to propped sheets of rotting plywood.

The sheer volume of wasted material and furniture in this large storage room on the western side of the complex is astounding. This place contains enough furniture, windows and doors to equip several houses. And it doesn't seem to be from the hotel itself; most of it's doors and windows are still in place. There are boxes of what appear to be new Pella window components, their contents rotting. Were these intended for the hotel's renovation into condos? Or did someone just use the big room as a repository for junk?

The bottommost part of the building has been largely boarded up, so it's harrowing in the central parts of the building. Entering into the

lobby is now an unsettling experience. We walked toward the only light, flooding in from plate glass windows on the eastern side. A

store front that once housed a small computer store, it was retrofitted with typical commercial building materials. Now, all the cheap dropped ceiling tiles have been ripped down, and one can see the hotel ornament underneath. Columns were stripped of ornament below where dropped ceilings would reach, in an ad-hoc renovation attempt. Walls have been haphazardly built to create smaller rooms for some long lost purpose.

Behind the lobby and the elevators is the kitchen area. Some bits of

the machinery are left: large ventilation fans, a gigantic oven, and a

beautiful, huge commercial gas range. From here one accesses the

service stair and elevator, circulation for all the staff of the

building. This multiplicity would be a good thing for fire codes in a

contemporary renovation. Amos and I used a more centrally located

stair, however, to access the upper parts of the building.

The higher I climbed, the less nervous I felt. I was, from the

beginning, a little more worried about psychopathic squatters inside

than cops outside, across the street at the North Precinct. The

Birmingham police have more important tasks than preventing bougieous

kids from sneaking into abandoned buildings.

The first few rooms we entered were predictably disgusting, the shag

The first few rooms we entered were predictably disgusting, the shag

carpet on the floor was soaked with rain, and the wallpaper was

peeling back, revealing a palimpsest of paint and what could only be

potent mold and mildew. I should mention here that both Amos and

myself were wearing those little white swine flu masks. I think it did

the job, i didn't have any sort of sick building symptoms when we

left, other than a little bit of a stuffy nose.

Walking through the halls and rooms, I was struck by how low the

ceilings are, and how poorly proportioned the individual rooms

themselves are. The typical Howard Johnson beside an interstate has

bigger rooms. And the bathrooms were small, cramped, and dark. I

wonder if this had some impact on the hotel's failure. It seems like

modern hotel-goers would want larger rooms, and parking. The building

just isn't quite special enough as a luxury hotel to justify the small

rooms. It feels very much like an office building of the same era.

Every floor is the same, every room is cramped, every hallway is a

tunnel. There are, however, some suites of rooms that are quite nice,

even though the individual rooms are the same proportions.

At about the 10th floor, I decided we should just haul ass to the roof. With more time, I would have explored each floor, but I was most

interested in getting up top, and checking out the iron mooring post, which is alleged to be for dirigibles. Next to this thing was the most

fascinating part of the building. Up on a platform was about 2 million strips of wood. Cursory research calls this a "water tower," but in reality this was a wooden coil for a cooling tower. It works pretty simply. Water was stored in the now rusty tanks, circulated through the building and then pumped back up to the roof and circulated through this wooden structure. In some of my photographs, it's possible to see the wood stacked in a lattice, which would have spread out the water for cooling. The gigantic, propeller sized fan would have blasted the water with air. It's basically an air conditioner, with water instead of refrigerant. Blow air over warm water, and the water is cooled. Run cool water through pipes, the pipes are cool, and the air is cooled. The problem with systems like this is condensation. The pipes are inevitably cooler than the air around them, and the pipe containing the water is below the dew point. Voila, you've got mold. It's doubtful the Thomas Jefferson Hotel was comfortable by today's arctic interior standards, but it's still an interesting system, that was probably relatively efficient.

Before heading back down, we poked around the elevator lifts, which have had (along with all the building's plumbing) their copper pilfered by some very diligent, destructive crackheads. It's a shame. and it's going to make renovation of this building that much more expensive and difficult. I worry about the structure, because it's really kind of a tall sore thumb, out of scale in that part of town. As that area gentrifies, there may be some developer who decides it's

financially viable to implode it and redevelop that block with idiotic stucco structures, like across the street from the former Parliament hotel.

But it's not doomed. The Thomas Jefferson/Cabana/Leer could be gutted,

and be inhabited again. Though it is rather dull on the interior, it

is a flexible building. It could work as an office or apartment, low

income housing or a hotel. Like so many of downtown Birmingham's

structures, it can become viable again as Alabamians realize they

don't have to drive cars and push to create walkable communities. The

early 20th century dream of vertical density can become something

exciting for Alabamians again.

-charles amos horn

to view compelete flickr photo set go here.